NSE Ticker

Friday, August 15, 2014

Thursday, August 14, 2014

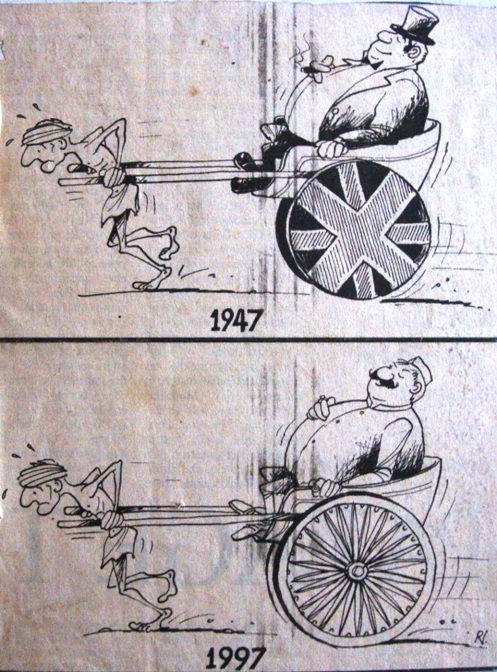

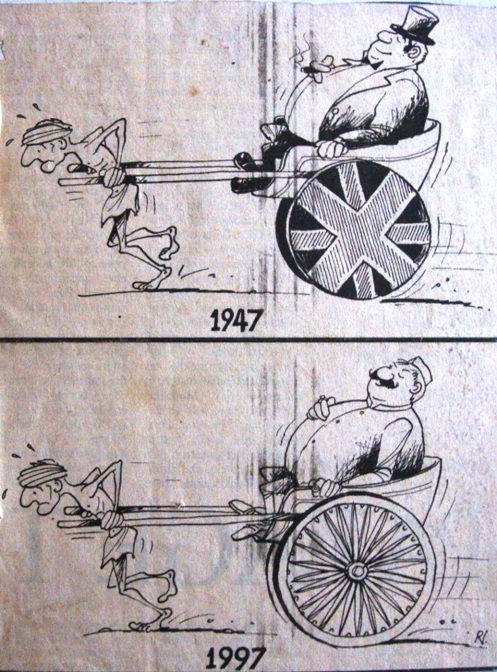

On the eve of Commemoration of 67 years of Independence Day of India

On the eve of

Commemoration

of 67 years of Independence Day of India

Courtesy : WIKIPEDIA

The economy of India is the tenth-largest in the world by nominal GDP and the third-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP).[3]

The country is one of the G-20 major economies, a member of BRICS and a developing economy that is among the top 20 global traders according to the WTO.[28]

India was the 19th-largest merchandise and the 6th largest services exporter in the world in 2013; it imported a total of $616.7 billion worth of merchandise and services in 2013, as the 12th-largest merchandise and 7th largest services importer.[29]

India's economic growth slowed to 4.7% for the 2013–14 fiscal year, in contrast to higher economic growth rates in 2000s.[30]

IMF projects India's GDP to grow at 5.4% over 2014-15.[31]

Agriculture sector is the largest employer in India's economy but contributes a declining share of its GDP (13.7% in 2012-13).[5] Its manufacturing industry has held a constant share of its economic contribution, while the fastest growing part of the economy has been its services sector - which includes construction, telecom, software and information technologies, infrastructure, tourism, education, health care, travel, trade, banking and others components of its economy.[6]

The post independence-era Indian economy (from 1947 to 1991) was a mixed economy with an inward-looking, centrally planned, interventionist policies and import-substituting economic model that failed to take advantage of the post-war expansion of trade and that nationalized many sectors of its economy.[32]

India's share of global trade fell from 1.3% in 1953 to 0.5% in 1983.[33] This model contributed to widespread inefficiencies and corruption, and it was poorly implemented.[34]

After a fiscal crisis in 1991, India has increasingly adopted free-market principles and liberalised its economy to international trade.

These reforms were started by former Finance minister Manmohan Singh under the Prime Ministership of P.V.Narasimha Rao.

They eliminated much of Licence Raj, a pre- and post-British era mechanism of strict government controls on setting up new industry.

Following these economic reforms, and a strong focus on developing national infrastructure such as the Golden Quadrilateral project by former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the country's economic growth progressed at a rapid pace, with relatively large increases in per-capita incomes.[35]

The south western state of Maharashtra contributes the highest towards India's GDP among all states, while Bihar is among its poorest states in terms of GNI per capita.

Mumbai is known as the trade and financial capital of India.[1][2][36]

India's gross national income

per capita had experienced high growth rates since 2002. India's Per

Capita Income has tripled from Rs. 19,040 in 2002–03 to Rs. 53,331 in

2010–11, averaging 13.7% growth over these eight years peaking 15.6% in

2010–11.[236]

However growth in the inflation adjusted Per capita income of the nation slowed to 5.6% in 2010–11, down from 6.4% in the previous year. These consumption levels are on an individual basis, not household.[237] On a household basis, the average income in India was $6,671 per household in 2011.[238]

Per 2011 census, India has about 330 million houses and 247 million households. The household size in India has dropped in recent years, with 2011 census reporting 50% of households have 4 or less members.

The average per 2011 census was 4.8 members per household, and included surviving grandparents.[239][240] These households produced a GDP of about $1.7 Trillion.[241] The household consumption patterns per 2011 census: approximately 67% of households use firewood, crop residue or cow dung cakes for cooking purposes; 53% do not have sanitation or drainage facilities on premises; 83% have water supply within their premises or 100 metres from their house in urban areas and 500 metres from the house in rural areas; 67% of the households have access to electricity; 63% of households have landline or mobile telephone connection; 43% have a television; 26% have either a two wheel (motorcycle) or four wheel (car) vehicle.

Compared to 2001, these income and consumption trends represent moderate to significant improvements.[239] One report in 2010 claimed that the number of high income households has crossed lower income households.[242]

The World Bank in 2010, using its older 2005 methodology, estimated about 400 million people in India, as compared to 1.29 billion people worldwide, live on less than $1.25 (PPP) per day. The World Bank reviewed and proposed revisions in May 2014, to its poverty calculation methodology and purchasing power parity basis for measuring poverty worldwide, including India. According to this revised methodology, the world had 872.3 million people below the new poverty line, of which 179.6 million people lived in India. In other words, India with 17.5% of total world's population, had 20.6% share of world's poorest in 2013.[10]

According to a 2005-2006 survey,[244] India had about 61 million children under the age of 5 who were chronically malnourished. A 2011 UNICEF report stated that that between 1990 to 2010, India achieved a 45 percent reduction in under age 5 mortality rates, and now ranks 46 in 188 countries on this metric.[245]

Since the early 1950s, successive governments have implemented various schemes to alleviate poverty, under central planning, that have met with partial success.[246] In 2005, Indian government enacted the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, guaranteeing 100 days of minimum wage employment to every rural household in all the districts of India.[247] In 2011, this Rural Employment Guarantee programme was widely criticised as no more effective than other poverty reduction programs in India.

Despite its best intentions, MGNREGA is beset with controversy about corrupt officials, deficit financing as the source of funds, poor quality of infrastructure built under this program, and unintended destructive effect on poverty.[248][249][250] Other studies suggest that the Rural Employment Guarantee welfare program has helped in reducing rural poverty in some cases.[251][252] Yet other studies report that India's economic growth has been the driver of sustainable employment and poverty reduction, but a sizable population remains in poverty.[253][254]

Of the total workforce, 7% is in the organised sector, two-thirds of which are in the government controlled public sector.[255] About 51.2% of the labor in India is self-employed.[12] According to 2005-06 survey, there is a gender gap in employment and salaries.

In rural areas, both men and women are primarily self-employed, mostly in agriculture.

In urban areas, salaried work was the largest source of employment for both men and women in 2006.[256]

Unemployment in India is characterised by chronic (disguised) unemployment.

Government schemes that target eradication of both poverty and unemployment (which in recent decades has sent millions of poor and unskilled people into urban areas in search of livelihoods) attempt to solve the problem, by providing financial assistance for setting up businesses, skill honing, setting up public sector enterprises, reservations in governments, etc. The decline in organised employment due to the decreased role of the public sector after liberalisation has further underlined the need for focusing on better education and has also put political pressure on further reforms.[257][258]

India's labour regulations are heavy even by developing country standards and analysts have urged the government to abolish or modify them in order to make the environment more conducive for employment generation.[259][260]

The 11th five-year plan has also identified the need for a congenial environment to be created for employment generation, by reducing the number of permissions and other bureaucratic clearances required.[261]

Further, inequalities and inadequacies in the education system have been identified as an obstacle preventing the benefits of increased employment opportunities from reaching all sectors of society.[262]

Child labour in India is a complex problem that is basically rooted in poverty. The Indian government has implemented, since the 1990s, a variety of programs to eliminate child labor. These have included setting up schools, launching free school lunch program, setting up special investigation cells and others.[263][264] Desai et al. state that recent studies on child labour in India have found some pockets of industries in which children are employed, but

overall, relatively few Indian children are employed. Child labor below the age of 10 is now rare. In the 10-14 group, the latest surveys find only 2% of children working for wage, while another 9% work within their home or rural farms assisting their parents in times of high work demand such as sowing and harvesting of crops.[265]

India has the second largest diaspora around the world, an estimated 25 million people,[266] many of whom work overseas and remit funds back to their families.

The Middle East region is the largest source of employment of expat Indians.

The crude oil production and infrastructure industry of Saudi Arabia employs over 2 million expat Indians.

Cities such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi in United Arab Emirates alone have employed another 2 million Indian construction workers during its construction boom in recent decades.[267] In 2009–10, remittances from Indian migrants overseas stood at 2500 billion (US$42 billion), the highest in the world, but their share in FDI remained low at around 1%.[268]

2500 billion (US$42 billion), the highest in the world, but their share in FDI remained low at around 1%.[268]

According to the World Bank, India's large agricultural subsidies are distorting what farmers grow and they are hampering productivity-enhancing investment.

While overregulation of agriculture has increased costs, price risks and uncertainty, governmental intervention in labour, land, and credit markets are hurting the market. Infrastructure such as rural roads, electricity, ports, food storage, retail markets and services are inadequate.[271]

Further, the average size of land holdings is very small, with 70% of holdings being less than one hectare in size.[272]

Irrigation facilities are inadequate, as revealed by the fact that only 39% of the total cultivable land was irrigated as of 2010,[102] resulting in farmers still being dependent on rainfall, specifically the monsoon season, which is often inconsistent and unevenly distributed across the country.[273]

Farmer incomes are low also in part because of lack of food storage and distribution infrastructure.

A third of India's agriculture produce is lost from spoilage.[180]

Corruption has been one of the pervasive problems affecting India. A 2005 study by Transparency International (TI) found that more than half of those surveyed had firsthand experience of paying bribe or peddling influence to get a job done in a public office in the previous year.[274]

A follow-on 2008 TI study found this rate to be 40 percent.[275] In 2011, Transparency International ranked India at 95th place amongst 183 countries in perceived levels of public sector corruption.[276]

In 1996, red tape, bureaucracy and the Licence Raj were suggested as a cause for the institutionalised corruption and inefficiency.[277]

More recent reports[278][279][280] suggest the causes of corruption in India include excessive regulations and approval requirements, mandated spending programs, monopoly of certain goods and service providers by government controlled institutions, bureaucracy with discretionary powers, and lack of transparent laws and processes.

The Right to Information Act (2005) which requires government officials to furnish information requested by citizens or face punitive action, computerisation of services, and various central and state government acts that established vigilance commissions, have considerably reduced corruption and opened up avenues to redress grievances.[274]

In 2011, the Indian government concluded that most spending fails to reach its intended recipients. A large, cumbersome and tumor-like bureaucracy sponges up or siphons off spending budgets.[281]

India's absence rates are one of the worst in the world; one study found that 25% of public sector teachers and 40% of government owned public sector medical workers could not be found at the workplace.[282][283]

Similarly, there are many issues facing Indian scientists, with demands for transparency, a meritocratic system, and an overhaul of the bureaucratic agencies that oversee science and technology.[284]

The Indian economy has an underground economy, with a 2006 report alleging that the Swiss Bankers Association suggested India topped the worldwide list for black money with almost $1,456 billion stashed in Swiss banks.

This amounts to 13 times the country's total external debt.[285][286]

These allegations have been denied by Swiss Banking Association. James Nason, the Head of International Communications for Swiss Banking Association, suggests

"The (black money) figures were rapidly picked up in the Indian media and in Indian opposition circles, and circulated as gospel truth.

However, this story was a complete fabrication.

The Swiss Bankers Association never published such a report. Anyone claiming to have such figures (for India) should be forced to identify their source and explain the methodology used to produce them."[287][288]

The right to education at elementary level has been made one of the fundamental rights under the eighty-sixth Amendment of 2002, and legislation has been enacted to further the objective of providing free education to all children.[290]

However, the literacy rate of 74% is still lower than the worldwide average and the country suffers from a high dropout rate.[291]

Further, the literacy rates and educational opportunities vary by region, gender, urban and rural areas, and among different social groups.[292][293]

Courtesy : WIKIPEDIA

The economy of India is the tenth-largest in the world by nominal GDP and the third-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP).[3]

The country is one of the G-20 major economies, a member of BRICS and a developing economy that is among the top 20 global traders according to the WTO.[28]

India was the 19th-largest merchandise and the 6th largest services exporter in the world in 2013; it imported a total of $616.7 billion worth of merchandise and services in 2013, as the 12th-largest merchandise and 7th largest services importer.[29]

India's economic growth slowed to 4.7% for the 2013–14 fiscal year, in contrast to higher economic growth rates in 2000s.[30]

IMF projects India's GDP to grow at 5.4% over 2014-15.[31]

Agriculture sector is the largest employer in India's economy but contributes a declining share of its GDP (13.7% in 2012-13).[5] Its manufacturing industry has held a constant share of its economic contribution, while the fastest growing part of the economy has been its services sector - which includes construction, telecom, software and information technologies, infrastructure, tourism, education, health care, travel, trade, banking and others components of its economy.[6]

The post independence-era Indian economy (from 1947 to 1991) was a mixed economy with an inward-looking, centrally planned, interventionist policies and import-substituting economic model that failed to take advantage of the post-war expansion of trade and that nationalized many sectors of its economy.[32]

India's share of global trade fell from 1.3% in 1953 to 0.5% in 1983.[33] This model contributed to widespread inefficiencies and corruption, and it was poorly implemented.[34]

After a fiscal crisis in 1991, India has increasingly adopted free-market principles and liberalised its economy to international trade.

These reforms were started by former Finance minister Manmohan Singh under the Prime Ministership of P.V.Narasimha Rao.

They eliminated much of Licence Raj, a pre- and post-British era mechanism of strict government controls on setting up new industry.

Following these economic reforms, and a strong focus on developing national infrastructure such as the Golden Quadrilateral project by former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the country's economic growth progressed at a rapid pace, with relatively large increases in per-capita incomes.[35]

The south western state of Maharashtra contributes the highest towards India's GDP among all states, while Bihar is among its poorest states in terms of GNI per capita.

Mumbai is known as the trade and financial capital of India.[1][2][36]

Income and consumption

Main article: Income in India

However growth in the inflation adjusted Per capita income of the nation slowed to 5.6% in 2010–11, down from 6.4% in the previous year. These consumption levels are on an individual basis, not household.[237] On a household basis, the average income in India was $6,671 per household in 2011.[238]

Per 2011 census, India has about 330 million houses and 247 million households. The household size in India has dropped in recent years, with 2011 census reporting 50% of households have 4 or less members.

The average per 2011 census was 4.8 members per household, and included surviving grandparents.[239][240] These households produced a GDP of about $1.7 Trillion.[241] The household consumption patterns per 2011 census: approximately 67% of households use firewood, crop residue or cow dung cakes for cooking purposes; 53% do not have sanitation or drainage facilities on premises; 83% have water supply within their premises or 100 metres from their house in urban areas and 500 metres from the house in rural areas; 67% of the households have access to electricity; 63% of households have landline or mobile telephone connection; 43% have a television; 26% have either a two wheel (motorcycle) or four wheel (car) vehicle.

Compared to 2001, these income and consumption trends represent moderate to significant improvements.[239] One report in 2010 claimed that the number of high income households has crossed lower income households.[242]

Per capita gross national income of India in 2013 compared to other

countries, on Purchasing Power Parity basis, per World Bank data.[243]

- Poverty

Main article: Poverty in India

The World Bank in 2010, using its older 2005 methodology, estimated about 400 million people in India, as compared to 1.29 billion people worldwide, live on less than $1.25 (PPP) per day. The World Bank reviewed and proposed revisions in May 2014, to its poverty calculation methodology and purchasing power parity basis for measuring poverty worldwide, including India. According to this revised methodology, the world had 872.3 million people below the new poverty line, of which 179.6 million people lived in India. In other words, India with 17.5% of total world's population, had 20.6% share of world's poorest in 2013.[10]

According to a 2005-2006 survey,[244] India had about 61 million children under the age of 5 who were chronically malnourished. A 2011 UNICEF report stated that that between 1990 to 2010, India achieved a 45 percent reduction in under age 5 mortality rates, and now ranks 46 in 188 countries on this metric.[245]

Since the early 1950s, successive governments have implemented various schemes to alleviate poverty, under central planning, that have met with partial success.[246] In 2005, Indian government enacted the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, guaranteeing 100 days of minimum wage employment to every rural household in all the districts of India.[247] In 2011, this Rural Employment Guarantee programme was widely criticised as no more effective than other poverty reduction programs in India.

Despite its best intentions, MGNREGA is beset with controversy about corrupt officials, deficit financing as the source of funds, poor quality of infrastructure built under this program, and unintended destructive effect on poverty.[248][249][250] Other studies suggest that the Rural Employment Guarantee welfare program has helped in reducing rural poverty in some cases.[251][252] Yet other studies report that India's economic growth has been the driver of sustainable employment and poverty reduction, but a sizable population remains in poverty.[253][254]

Employment

See also: Labour in India, Indian labour law and Child labour in India

Agricultural and allied sectors accounted for about 52.1% of the

total workforce in 2009–10. While agriculture employment has fallen over

time in percentage of labor employed, services which includes

construction and infrastructure have seen a steady growth accounting for

20.3% of employment in 2012-13.[12] Of the total workforce, 7% is in the organised sector, two-thirds of which are in the government controlled public sector.[255] About 51.2% of the labor in India is self-employed.[12] According to 2005-06 survey, there is a gender gap in employment and salaries.

In rural areas, both men and women are primarily self-employed, mostly in agriculture.

In urban areas, salaried work was the largest source of employment for both men and women in 2006.[256]

Unemployment in India is characterised by chronic (disguised) unemployment.

Government schemes that target eradication of both poverty and unemployment (which in recent decades has sent millions of poor and unskilled people into urban areas in search of livelihoods) attempt to solve the problem, by providing financial assistance for setting up businesses, skill honing, setting up public sector enterprises, reservations in governments, etc. The decline in organised employment due to the decreased role of the public sector after liberalisation has further underlined the need for focusing on better education and has also put political pressure on further reforms.[257][258]

India's labour regulations are heavy even by developing country standards and analysts have urged the government to abolish or modify them in order to make the environment more conducive for employment generation.[259][260]

The 11th five-year plan has also identified the need for a congenial environment to be created for employment generation, by reducing the number of permissions and other bureaucratic clearances required.[261]

Further, inequalities and inadequacies in the education system have been identified as an obstacle preventing the benefits of increased employment opportunities from reaching all sectors of society.[262]

Child labour in India is a complex problem that is basically rooted in poverty. The Indian government has implemented, since the 1990s, a variety of programs to eliminate child labor. These have included setting up schools, launching free school lunch program, setting up special investigation cells and others.[263][264] Desai et al. state that recent studies on child labour in India have found some pockets of industries in which children are employed, but

overall, relatively few Indian children are employed. Child labor below the age of 10 is now rare. In the 10-14 group, the latest surveys find only 2% of children working for wage, while another 9% work within their home or rural farms assisting their parents in times of high work demand such as sowing and harvesting of crops.[265]

India has the second largest diaspora around the world, an estimated 25 million people,[266] many of whom work overseas and remit funds back to their families.

The Middle East region is the largest source of employment of expat Indians.

The crude oil production and infrastructure industry of Saudi Arabia employs over 2 million expat Indians.

Cities such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi in United Arab Emirates alone have employed another 2 million Indian construction workers during its construction boom in recent decades.[267] In 2009–10, remittances from Indian migrants overseas stood at

Agriculture

Main article: Agriculture in India

Agriculture is an important part of Indian economy. In 2008, a New

York Times article claimed, with the right technology and policies,

India could contribute to feeding not just itself but the world.

However, agricultural output of India lags far behind its potential.[270] The low productivity in India is a result of several factors. According to the World Bank, India's large agricultural subsidies are distorting what farmers grow and they are hampering productivity-enhancing investment.

While overregulation of agriculture has increased costs, price risks and uncertainty, governmental intervention in labour, land, and credit markets are hurting the market. Infrastructure such as rural roads, electricity, ports, food storage, retail markets and services are inadequate.[271]

Further, the average size of land holdings is very small, with 70% of holdings being less than one hectare in size.[272]

Irrigation facilities are inadequate, as revealed by the fact that only 39% of the total cultivable land was irrigated as of 2010,[102] resulting in farmers still being dependent on rainfall, specifically the monsoon season, which is often inconsistent and unevenly distributed across the country.[273]

Farmer incomes are low also in part because of lack of food storage and distribution infrastructure.

A third of India's agriculture produce is lost from spoilage.[180]

Corruption

Corruption

Corruption

Main article: Corruption in India

Corruption has been one of the pervasive problems affecting India. A 2005 study by Transparency International (TI) found that more than half of those surveyed had firsthand experience of paying bribe or peddling influence to get a job done in a public office in the previous year.[274]

A follow-on 2008 TI study found this rate to be 40 percent.[275] In 2011, Transparency International ranked India at 95th place amongst 183 countries in perceived levels of public sector corruption.[276]

In 1996, red tape, bureaucracy and the Licence Raj were suggested as a cause for the institutionalised corruption and inefficiency.[277]

More recent reports[278][279][280] suggest the causes of corruption in India include excessive regulations and approval requirements, mandated spending programs, monopoly of certain goods and service providers by government controlled institutions, bureaucracy with discretionary powers, and lack of transparent laws and processes.

The Right to Information Act (2005) which requires government officials to furnish information requested by citizens or face punitive action, computerisation of services, and various central and state government acts that established vigilance commissions, have considerably reduced corruption and opened up avenues to redress grievances.[274]

In 2011, the Indian government concluded that most spending fails to reach its intended recipients. A large, cumbersome and tumor-like bureaucracy sponges up or siphons off spending budgets.[281]

India's absence rates are one of the worst in the world; one study found that 25% of public sector teachers and 40% of government owned public sector medical workers could not be found at the workplace.[282][283]

Similarly, there are many issues facing Indian scientists, with demands for transparency, a meritocratic system, and an overhaul of the bureaucratic agencies that oversee science and technology.[284]

The Indian economy has an underground economy, with a 2006 report alleging that the Swiss Bankers Association suggested India topped the worldwide list for black money with almost $1,456 billion stashed in Swiss banks.

This amounts to 13 times the country's total external debt.[285][286]

These allegations have been denied by Swiss Banking Association. James Nason, the Head of International Communications for Swiss Banking Association, suggests

"The (black money) figures were rapidly picked up in the Indian media and in Indian opposition circles, and circulated as gospel truth.

However, this story was a complete fabrication.

The Swiss Bankers Association never published such a report. Anyone claiming to have such figures (for India) should be forced to identify their source and explain the methodology used to produce them."[287][288]

Education

Main article: Education in India

India has made huge progress in terms of increasing primary education attendance rate and expanding literacy to approximately three-fourths of the population.[289]

India's literacy rate had grown from 52.2% in 1991 to 74.04% in 2011. The right to education at elementary level has been made one of the fundamental rights under the eighty-sixth Amendment of 2002, and legislation has been enacted to further the objective of providing free education to all children.[290]

However, the literacy rate of 74% is still lower than the worldwide average and the country suffers from a high dropout rate.[291]

Further, the literacy rates and educational opportunities vary by region, gender, urban and rural areas, and among different social groups.[292][293]

Monday, August 4, 2014

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy correct : Economic Times

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy correct : Economic Times

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy and stocking policies threaten to derail progress on multilateral trade as envisaged under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. Or that is what the West would want the world to believe.

The truth, however, is more nuanced and has to do with overwhelming national priorities, not so-called free trade. "Free trade" is a term used opportunistically when developed countries want other nations to open up markets for their products and services.

Yet, economic historians know that both Britain and the US favoured protectionist policies to foster economic growth during their development phases. Abraham Lincoln favoured a 44 per cent tariff during the American civil war to starve the more prosperous south of industrial products and build railways in the north. And Franklin Roosevelt would go on to blame protectionism under his predecessor as one of the causal factors of the Great Depression. India's main priority is to buy food at support prices from farmers, more than 50 per cent of the population, stock it and supply it to the poor at low prices.

Yet, WTO rules say that these subsidies cannot cross 10 per cent of the value of food output. This is utter rubbish, because the pricing is calculated at rates set in 1986-88, which artificially lower the food subsidy ceiling. India cannot agree to such terms.

When Europe and the US ask India to cut subsidies and tariffs in food and agriculture markets, we should ask why they persist with high tariff and non-tariff barriers to protect their farm sector, which is also heavily subsidised. India's stand on trade talks is correct and justified by our national priorities. Developed countries have to open up their markets to freer movement of goods, workers and services from developing ones. Pressure to cut food subsidies in India has to be matched by opening up of food and farm markets in the West.

In any case, this story is not over as yet. India is willing to go back to the negotiating table in September when the WTO reopens, and if other nations agree to postpone curbs on India's food subsidies, talks can progress.

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy and stocking policies threaten to derail progress on multilateral trade as envisaged under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. Or that is what the West would want the world to believe.

The truth, however, is more nuanced and has to do with overwhelming national priorities, not so-called free trade. "Free trade" is a term used opportunistically when developed countries want other nations to open up markets for their products and services.

Yet, economic historians know that both Britain and the US favoured protectionist policies to foster economic growth during their development phases. Abraham Lincoln favoured a 44 per cent tariff during the American civil war to starve the more prosperous south of industrial products and build railways in the north. And Franklin Roosevelt would go on to blame protectionism under his predecessor as one of the causal factors of the Great Depression. India's main priority is to buy food at support prices from farmers, more than 50 per cent of the population, stock it and supply it to the poor at low prices.

Yet, WTO rules say that these subsidies cannot cross 10 per cent of the value of food output. This is utter rubbish, because the pricing is calculated at rates set in 1986-88, which artificially lower the food subsidy ceiling. India cannot agree to such terms.

When Europe and the US ask India to cut subsidies and tariffs in food and agriculture markets, we should ask why they persist with high tariff and non-tariff barriers to protect their farm sector, which is also heavily subsidised. India's stand on trade talks is correct and justified by our national priorities. Developed countries have to open up their markets to freer movement of goods, workers and services from developing ones. Pressure to cut food subsidies in India has to be matched by opening up of food and farm markets in the West.

In any case, this story is not over as yet. India is willing to go back to the negotiating table in September when the WTO reopens, and if other nations agree to postpone curbs on India's food subsidies, talks can progress.

support

prices from farmers, more than 50 per cent of the population, stock it

and supply it to the poor at low prices. Yet, WTO rules say that these

subsidies cannot cross 10 per cent of the value of food output.

This is utter rubbish, because the pricing is calculated at rates set in 1986-88, which artificially lower the food subsidy ceiling. India cannot agree to such terms. When Europe and the US ask India to cut subsidies and tariffs in food and agriculture markets, we should ask ..

This is utter rubbish, because the pricing is calculated at rates set in 1986-88, which artificially lower the food subsidy ceiling. India cannot agree to such terms. When Europe and the US ask India to cut subsidies and tariffs in food and agriculture markets, we should ask ..

India's

refusal to dilute its food subsidy and stocking policies threaten to

derail progress on multilateral trade as envisaged under World Trade

Organization (WTO) rules. Or that is what the West would want the world

to believe.

The truth, however, is more nuanced and has to do with overwhelming national priorities, not so-called free trade. "Free trade" is a term used opportunistically when developed countries want other nations to open up markets for their products and ..

The truth, however, is more nuanced and has to do with overwhelming national priorities, not so-called free trade. "Free trade" is a term used opportunistically when developed countries want other nations to open up markets for their products and ..

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy correct

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy correct

By ET Bureau | 4 Aug, 2014, 01.40AM IST

Read more at:

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/39572587.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/39572587.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy correct

India's refusal to dilute its food subsidy correct

By ET Bureau | 4 Aug, 2014, 01.40AM IST

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)